On September 23, 1999, after five years of development and nine and a half months of travel, the ‘Mars Climate Orbiter’ crashed into the atmosphere of Mars. For days no one found the fault behind the accident. The explanation was as simple as it was incredible: someone had forgotten to convert the data from the imperial system to the metric system, that is, to the international system of units. One hundred twenty-five million dollars were thrown away.

That of the ‘Mars Climate’ is one of the classic examples of all those who consider metric standardization “one of the most complex social and intellectual projects that have ever existed.” And yes, I am referring to people like me. However, in recent years I have begun to think about the arguments of certain experts who point out that many measurement units that seem strange and out of date have good arguments behind them … What if we SIU fanboys were wrong? Let’s talk about the temperature.

Kelvin, Celsius, Fahrenheit, and vice versa

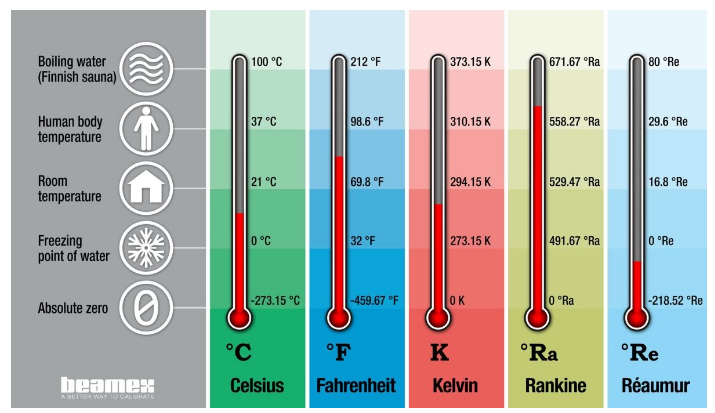

Neither the degree Fahrenheit nor the degree Celsius are ‘base units’ of the International System of Units. The latter does appear as a “derived unit,”; but the key unit of thermodynamic temperature is the Kelvin. This unit was created in 1848 by William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, based on the degree Celsius, but taking absolute zero (−273.15 °C) as a reference instead of the freezing point of water.

Not that that means much to most of the world, of course. While Kelvin rules technical documents, most of the world gets by with degrees Celsius without much trouble. The ‘Fahrenheit’ is, to put it in some way, an almost exclusively North American rarity. Created by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit in 1724 to find a standardizable way to use the thermometer he had just designed, these degrees are indeed arbitrary.

There are several theories about how these degrees arose, but it is usually said that obsessed with eliminating the negative degrees on the Rømer scale, he took the coldest temperature he could find as zero and took the growth of 0.0001% of the temperature as his unit. The volume of mercury from your thermometer. Among other things, and according to the popular journals of the American Physical Society, he would make the Fahrenheit scale more intuitive in everyday life.

There is a whole rosary of arguments ranging from human problems with decimal numbers ( Sinnot et al., 2013 ; ) (and how the greater sensitivity of degrees Fahrenheit would allow us to use fewer decimal places when talking about temperature) to its adequacy to improve the communication of climate change problems. All are more than debatable arguments.

However, they have a suggestive one. And it is that although the freezing point and the boiling point are relevant in the scientific world (and in the kitchen), in everyday life, they do not tell us much about the temperatures in which people live. If we look at the average temperatures for the city of Vancouver, we see that the histograms of daily temperatures span the range of -17 to 27°C vs. 18 to 80°F. Theoretically, this last range would be much more manageable. Theoretically, always according to the APS, Fahrenheit would be more manageable.

Objectivity vs utility

Personally, the argument does not quite convince me either. However, it raises something interesting. Before the 1789 Revolution, there were 250,000 different units of measurement in France alone. It was something that happened everywhere. In Spain, as José Manuel Blanco recounts, a pound weighed 351 grams in Huesca, 575 in Coruña, or 372 in Pamplona. The process of creating a system that prevented fraud and deception focused more on building measures that we could easily objectify than on useful measures.

We have sought ‘objectivity’ above ‘utility’. As in the old joke, for hundreds of years, we have been like the drunk who looks for the keys near a streetlight even though he lost them elsewhere for the simple fact that near the streetlight is where the light is. Now that we have practically completed the great project of building the units with which to measure the world, perhaps it would be time to use the “derived units” to build that world on a human scale. I’m not sure it leads us anywhere interesting, but it’s worth exploring.

Sharlene Meriel is an avid gamer with a knack for technology. He has been writing about the latest technologies for the past 5 years. His contribution in technology journalism has been noteworthy. He is also a day trader with interest in the Forex market.